Eli Levine, Chavez Cheong, Ridge Ren, Emily Leung, Sam Wolter

According to the 2000 Census, the state of Washington possessed 2.45 million housing units.[1] Out of the occupied housing units, 64.6 percent were owner-occupied while 35.4 percent were renter-occupied. By 2010, the number of housing units in Washington had grown to almost 2.89 million[2] and the state became more diverse, with the share of the population identifying as “non-Hispanic white” declining from 78.9 percent to 72.5 percent.[3]

In the years leading up to the crisis, the homeownership rate in Washington remained lower than the national average, and tracked national trends. In 2002, the monthly median household income in Washington was $63,243, almost $4,000 more than the national median household income of $59,360. Median income in the state continued to increase throughout the decade at a level exceeding the national average

Figure 1: Home Ownership Rate for Washington and for the United States (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

Figure 2: Real Median Household Income in Washington and in the United States (US Census Bureau)

Washington home prices exceeded the national average in the decade preceding the financial crisis, with the gap accelerating in 2006.

Figure 3 All-Transactions House Price Index for Washington and for the United States (Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis)

Mortgage Enforcement Actions (MEAs) in the state of Washington are issued by the Division of Consumer Services within the Washington State Department of Financial Institutions (DFI).[4] A gubernatorial appointment subject to confirmation by the state senate, the DFI Director oversees the department. The agency issues frequent consumer alerts on scams and rules violations, allows consumers to file complaints and verify licenses, and sanctions rule-breaking companies.7 The DFI has the authority to prohibit firms and individuals from doing business in the industry, to impose fines, to order restitutions, and to collect investigation fees. The DFI regulates across the financial spectrum, ranging from banking to securities to consumer services. Its authorizing legislation grants it “all powers, duties, and functions…pertaining to duties relating to banks, savings banks, foreign bank branches, savings and loan associations, credit unions, consumer loan companies, check cashers and sellers, trust companies and departments, and other similar institutions.”[5] Similarly, it exercises “all powers, duties, and functions” pertaining to the regulation of “escrow agents, securities, franchises, business opportunities, commodities, and any other speculative investments.”[6]

According to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Washington State regulations on mortgage brokers were consistent in their level of restrictiveness from 1996 to 2006. The Mortgage Broker Practices Act (MBPA), codified in the Revised Code of Washington (RCW) at Chapter 19.146, governs the conduct of entities involved in the origination and brokering of residential real estate loans.[7] Its purpose was to “establish a state system of licensure” for mortgage brokers and loan originators, so as “to promote honesty and fair dealing with citizens and to preserve public confidence in the lending and real estate community.”[8] MBPA regulates who can do business, specifies what kind of interactions mortgage brokers and originators are allowed to have with their clients, defines the key term, “residential mortgage,” and offers parameters that determine which brokers/clients and what type of transactions are covered under the statute. [9] Each mortgage broker applicant must appoint a “Designated Broker,” who in turn must have two years of experience and must have successfully passed the Washington Designated Broker Test, administered by Pearson VUE, a private testing company. Since 2008, Washington state has required applicants to submit their application materials, including testing and disclosures, through the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System (NMLS).[10] The MBPA also creates a mechanism to ensure the financial credibility of mortgage brokers in the form of a surety bond. While some states establish a specified bond amount, Washington law instead requires a more tailored approach calibrating the amount required “according to the annual loan origination volume of the licensee.”[11]

In addition to 19.146, there are several other chapters that regulate residential mortgage lending in Washington. The Consumer Loan Act, codified in RCW 31.04(CLA), regulates a wide range of common consumer loan entities, including “mortgage loan originators.” The act defines a mortgage loan originator as an individual “who for compensation or gain (i) takes a residential mortgage loan application, or (ii) offers or negotiates terms of a residential mortgage loan” or who holds themselves out as able to perform any of these functions.[12] It thus broadens protection for borrowers by regulating non-broker mortgage lenders. RCW 19.144, entitled Mortgage Lending and Homeownership, focuses on substantive regulation of mortgage terms and features rather than the licensing and regulation of individual lenders. For example, it bans the making of mortgage loans that impose negative amortization[13] and strictly limits prepayment penalties.[14] Finally, there are separate regulations for Mortgage Loan Servicing, codified in RCW 19.148. These regulations require various disclosures when the servicing of a loan is sold or transferred.[15]

All Mortgage Enforcement Actions (MEAs) that we analyzed between 2002 and 2010 were the result of violations of the Washington Mortgage Broker Practices Act. The most common MEAs were “Final Order with attached Statement of Charges” and “Consent Order with attached Statement of Charges.” A Final Order represents the final determination in a case by the hearing examiner presiding over the administrative action.[16] A consent order represents a negotiated agreement between the Department of Financial Institutions and the offending party.

Figure 4 : Distribution of MEAs by Type of Orders

https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions[17]

Figure 4 highlights how infrequent MEAs were prior to 2007 and the dramatic increase in MEAs that accompanied the bursting of the housing bubble. Final order and consent order with attached statement of charges show the largest spikes. Additional research is needed to help identify the factors driving this increase. Possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive, include: a heightened enforcement posture by the Department of Financial Institutions once the bubble burst; entry of more unscrupulous actors into the housing finance sector during the pre-crisis boom years; and the erosion of ethical practices at established firms amidst a nationwide underwriting frenzy.

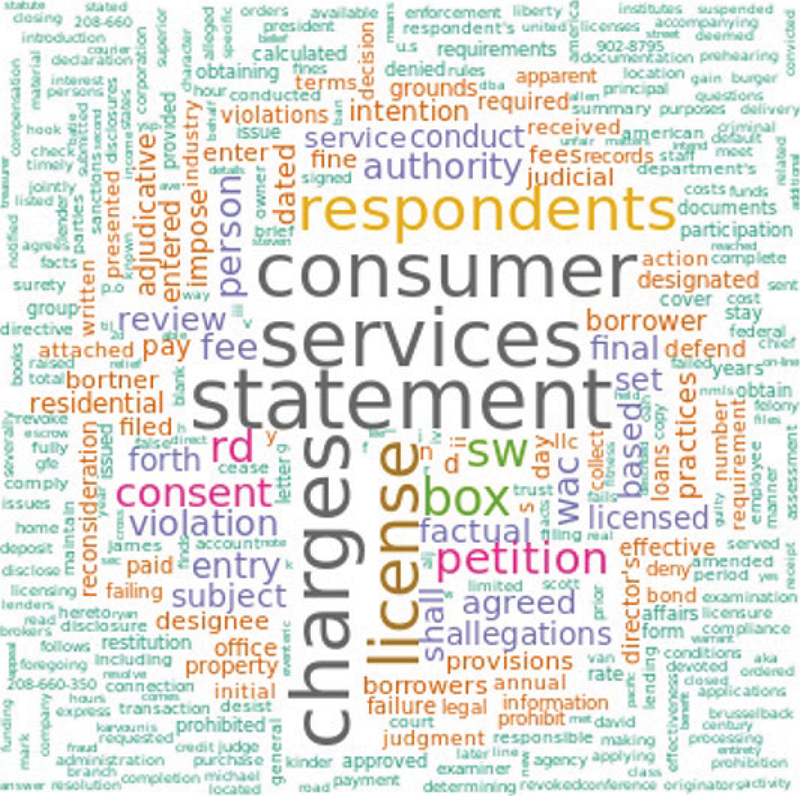

We conducted natural language processing to find the most common words in Washington MEAs and the main topics within them.

Figure 5 Word Cloud for Washington MEAs

https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions[18]

The most common words in these MEAs are “consumer,” “services,” “statements,” and “charges.” These words are frequent in legal documents concerning consumer rights and financial services. This makes sense in the context of mortgage enforcement actions, which are essentially administrative court orders against mortgage brokers alleged to have violated mortgage laws. The secondary level of words includes “respondents,” “license,” “petition,” “authority,” “consent,” and” violation.” “License” is a frequent term, likely because many of the mortgage regulation violations were due to brokers conducting business without a license. Revocation of license is a common punishment for violating the Mortgage Broker Practices Act. “Petition”[19] refers to the right for recipients to appeal for reconsiderations under RCW 34.05.470. “Authority” frequently appears when the courts cite the statutes that give them the power to issue fines or revocation of licenses. “Consent” is in the title of many of these consent orders, which reflect negotiated agreements to resolve an administrative action, often without an admission of guilt or liability. “Violation” refers to the regulations that have been breached by the party receiving the MEAs.

Figure 6 Breakdown of MEAs by Offense Classification Over Time

https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions[20]

The graph above plots the types of MEA offenses over time from 2002 to 2012. The failure to fulfill annual assessment reached a high point before decreasing in 2005. MEAs issued for failing to file the required annual broker report steadily rose beginning in 2006 and peaked in 2010.

Figure 7 Distribution of MEA Offenses

https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions[21]

The graph above shows the most frequent offenses listed in the Washington MEAs. MEAs can cover multiple offenses by a single recipient. The most common offenses were operating without a license, having a felony conviction, theft, money laundering, and failing to file the annual broker report. Commonly issued punishments for these offenses were fines, investigation fees, and suspension of licenses. Interestingly, “misleading borrowers” was not cited as an offense in a majority of the MEAs.

All of Washington’s MEAs resulted from authority vested by the state’s MBPA.[22] Over the years, there were some minor amendments to that statute, but the changes are difficult to track. Washington’s decision to combine multiple documents into single pdfs when they were issued against the same party can also affect our data on the most frequent offenders. Additionally, some MEAs were issued based on uncategorized offenses. Knowing exactly what those offenses were would enhance our understanding of the mortgage crisis in the state of Washington.

Mortgage enforcement actions in the state of Washington slowly increased in the run-up to the financial crisis and skyrocketed when the housing bubble burst. As the housing market in the state heated up, it may have attracted more unlicensed mortgage brokers and mortgage brokers with felony convictions.

[1] “Washington: 2000.” United States Census 2000 Report, United States Census Bureau, 2002.

[2] “Washington: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts.” 2010 Census of Population and Housing, United States 2010 Census, Aug. 2012.

[3] “Washington State Population: Where We Are Since 2000.” Office of Financial Management, Washington State, 2010.

[4] “For Consumers.” Washington State Department of Financial Institutions, Washington State Department of Financial Institutions.

[5] RCW 43.320.011: Department of General Administration and Department of Licensing Powers and Duties Transferred.

[6] “Mortgage Brokers.” Washington State Department of Financial Institutions, Washington State Department of Financial Institutions.

[7] Pahl, Cynthia. “A Compilation of State Mortgage Broker Laws and Regulations, 1996–2006.” Federal Reserve Bank OF Minneapolis Community Affairs Report, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Oct. 2007.

[9] “Mortgage Broker Practices Act.” Chapter 19.146 RCW: Mortgage Broker Practices Act, Washington State Legislature.

[10] https://dfi.wa.gov/mortgage-brokers/licensing; RCW 19.146.390

[17] https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions

[18] https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions

[19] “RCWs Title 34 Chapter 34.05 Section 34.05.470.” RCW 34.05.470: Reconsideration., Washington State, 1989.

[20] https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions

[21] https://dfi.wa.gov/enforcement-actions